|

Conflicting Reports on Human Cloning

One Study Claims a Clone, Another Says Technique Fatally Flawed

Listen to Joe Palca's report. Listen to Joe Palca's report.

A new report in the journal Science suggests creating a cloned human embryo may currently be impossible. But Dr. Panayiotis Zavos, pictured above left at a congressional hearing on cloning, says in another journal that he has done exactly that.

Photo: PBS/Online Newshour

|

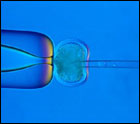

A nucleus is removed from an egg. In the process of cloning, the cell nucleus of the organism being cloned is inserted into a donor egg whose nucleus has been removed.

Photo: Roslin Institute

|

Once the nucleus is inserted into the egg, a series of chemicals are then added to trick the egg into thinking it's been fertilized.

See a detailed illustration of the process. Graphic: FASEB

|

April 10, 2003 --

Two scientific papers out this week are at odds on the question of whether it will be possible to clone human beings. A study published in the journal Science suggests that cloning primates -- a group of animals that includes humans -- is nearly impossible using current methods. But earlier this week, a fertility doctor in Kentucky reported that he had successfully created a very early human embryo clone. NPR's Joe Palca reports.

A University of Pittsburgh team led by Gerald Schatten has been trying to clone monkeys for some time, but without success. One of the reasons, Schatten reports in Science, is that monkey eggs are different from other animal eggs in which cloning has succeeded.

The current method of cloning uses techniques first devised by Scottish scientists to make Dolly the cloned sheep. Researchers remove chromosomes containing DNA from an egg, and replace it with chromosomes taken from the adult animal that's being cloned. If the procedure works, the resulting embryo starts to grow.

But Schatten found that in monkey eggs, when chromosomes are removed, crucial proteins are inevitably removed with them. These egg proteins are necessary for an embryo to develop normally. With the proteins missing from the egg, the inserted chromosomes can't function properly.

"The net result is that you end up with an egg that doesn't have the machinery to separate chromosomes accurately," says Schatten. In a sense, the egg is "almost paralyzed, so the embryo that results has no reproductive potential."

Schatten's team found that the cloned monkey embryos would only grow briefly in the laboratory, and weren't able to develop into a baby animal.

Schatten says he doesn't know why these egg proteins in primates appear to behave differently from other species.

"I sometimes joke," says Schatten, "that God in her infinite wisdom said 'I will let you clone domestic species for agriculture, and I will let you clone mice and even a cat to catch the cloned mice. But I draw a sharp line between primates and all other mammals.' "

If Schatten's right, that sheds some doubt on a new report in the journal Reproductive BioMedicine Online. In it, self-proclaimed human cloner Panayiotis Zavos says he has made an eight-to-10 cell human embryo that he has frozen for future analysis. Zavos, who could not be reached for comment, presents no evidence about whether the chromosomes in his embryo are normal.

Schatten says he's certain they are not: "Even though you can derive embryos that are seemingly normal, at a chromosomal level they are completely anomalous, and have no reproductive potential."

It's also possible that Schatten's explanation about why cloning won't work in primates is wrong.

"This is certainly a possible explanation," says Randall Prather, a cloning scientist at the University of Missouri. "It needs to be followed up... it might not be the only problem. There may be other things, too."

Scientists have had to modify cloning techniques that worked for Dolly the sheep to make them work on cows and mice and other species that have been cloned.

And George Daley at the Whitehead Institute in Cambridge says even if Schatten is right, it doesn't spell the end of the line for primate cloning.

"This doesn't prove that it will never work, and that current failure won't be replaced by future technical success," Daley says. "Someone else using different methodology could potentially solve this problem."

Online Discussion

Post your thoughts or questions about human cloning at NPR's discussion board.

|