|

The Lure of the Bean

Don't Believe Caffeine's a Drug? Just Ask Balzac

Listen as Scott Simon talks to Bennett Alan Weinberg. Listen as Scott Simon talks to Bennett Alan Weinberg.

Sept. 8, 2001 -- "Coffee is a great power in my life," wrote Honore de Balzac. "I have observed its effects on an epic scale."

He wasn't kidding. The great and prolific French writer known for his conspicuous consumption of coffee "was unquestionably a drug addict," write Bennett Alan Weinberg and Bonnie K. Bealer in their book, The World of Caffeine: The Art and Science of the World's Most Popular Drug. "His drug of choice was caffeine."

|

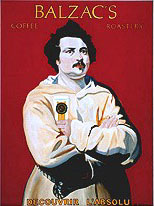

Balzac was as prolific a coffee-consumer as he was a writer. He is so famous for it that his image is often used to peddle beans.

Image courtesy Arlene Crooks-Best. | Before you pooh-pooh the notion that caffeine is a drug in every sense of the word, rest assured that Balzac's own eyes were wide open on the matter. "For awhile," he wrote, "for a week or two at most, you can obtain the right amount of stimulation with one, then two cups of coffee brewed from beans that have been crushed with gradually increasing force and infused with hot water. For another week, by decreasing the amount of water used, by pulverizing the coffee even more finely, and by infusing the grounds with cold water, you can continue to obtain the same cerebral power."

He's not talking here about how great the stuff tastes. And although he used coffee to aid in his writing -- by stimulating his imagination and by keeping him awake and hunched over his parchment through the night -- he had no illusions that there were no drawbacks to his favorite drug: "Many people claim that coffee inspires them, but, as everybody knows, coffee only makes boring people even more boring."

Anybody who has spent any time among cocaine fiends will recognize Balzac's complaint. Still don't believe caffeine is a drug?

In the end, Balzac resorted to eating dry coffee grounds to achieve the desired effect. He died at age 49.

Most people aren't like Balzac, and most people who use caffeine in its many forms -- coffee, tea, chocolate, soft drinks -- use it far more moderately. Some drugs are worse than others, and the world has decided that caffeine isn't so bad.

As author Weinberg tells Weekend Edition Saturday's Scott Simon, the origins of coffee -- the favored caffeine-delivery mechanism in much of the world -- are somewhat hazy. Coffee appeared "very suddenly and rather mysteriously" in Yemen at the end of the 15th century, he says. "Where it came from, exactly, isn't quite clear."

But it caught on pretty quickly. "Within 100 years, it had taken over the Arab world, and in another 100 years, it had taken over just about the whole world."

Caffeine's effect went much further than just giving the world a buzz, Weinberg says. It changed attitudes about economics and working life, and it may have helped provide inspiration for ideas that laid the groundwork for industrialism. The first accurate timepieces were invented at just about the same that coffee became popular. At the same time, coffee and tea -- so-called "temperance beverages" -- managed to replace alcohol in many people's diets, markedly increasing productivity.

If coffee was the fuel of the Industrial Revolution, it's even more central to the information economy. It is, says Weinberg, "the cult drug of the computer world." Drunk in moderation, it provides "specific cognitive benefits that allow people to perform computer work better. It aids in visual spatial coordination, hand-eye coordination, and it helps improve your reasoning power."

If Balzac is to be believed, the effects can be even more profound -- almost mystical -- for literary types. For a writer under the spell of the bean, he wrote, "ideas quick-march into motion like battalions of a grand army to its legendary fighting ground, and the battle rages. Memories charge in, bright flags on high; the cavalry of metaphor deploys with a magnificent gallop, the artillery of logic rushes up with clattering wagons and cartridges; on imagination's orders, sharpshooters sight and fire; forms and shapes and characters rear up; the paper is spread with ink -- for the nightly labor begins and ends with torrents of this black water."

Other Resources

•The Caffeine Archive is filled to the brim with links to all kinds of caffeine-related Web sites.

•Too Much Coffee Man is a comic hero for the information age.

•Fresh Cup magazine examines American coffee culture.

|