Jack Kerouac Multimedia |

|

|

Watch a video clip of Jack Kerouac reading from On the Road on The Steve Allen Plymouth Show in 1959. (From Kerouac, a Film by John Antonelli © 1995 John Antonelli and Mystic Fire Video) |

|

Hear Kerouac read from On the Road (Jazz of the Beat Generation). (From Jack Kerouac Reads On the Road © 1999 Rykodisc) |

|

Listen to Kerouac read from On the Road and Visions of Cody, accompanied on piano by Steve Allen on The Steve Allen Plymouth Show in 1959. (From The Jack Kerouac Collection © 1990 Rhino Records) |

Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady Tapes In the early 1950s, Jack Kerouac lived with Neal and Carolyn Cassady in northern California. Before Jack arrived, Neal had purchased a new tape recorder hoping he and Jack could send tapes back and forth to each other as an alternative to their frequent letter writing. Once Kerouac moved in, they would often amuse themselves recording their conversations or reading aloud to each other from various books. Cassady's widow, Carolyn, says the recorder was rolling all the time, but they could only afford a few reels of blank tape, so they would often record over earlier recordings. Of all the recordings they made, Carolyn Cassady retains only a 15-minute fragment. She told NPR's Renée Montagne the tape was recorded in 1952 at their home in San Jose. Selections from that fragment follow. Tape courtesy Carolyn Cassady |

|

|

Hear Kerouac sing "My Funny Valentine." |

|

Listen to Kerouac read from his novel Dr. Sax. (Neal Cassady can be heard in the background, rooting Kerouac on.) |

|

Hear Neal Cassady discuss their friend, the writer William Burroughs. |

|

Kerouac's On the Road

Listen to Renée Montagne's report. Listen to Renée Montagne's report.

Explore Jack Kerouac multimedia resources. Explore Jack Kerouac multimedia resources.

Read excerpts from On the Road. Read excerpts from On the Road.

Listen to rare tapes of Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady. Listen to rare tapes of Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady.

|

Sept. 9, 2002 -- The story couldn't help but give birth to a legend. Jack Kerouac, fueled by inspiration, coffee and Benzedrine, sat down at his typewriter and in one burst of creative energy wrote the novel that would make him the voice of his generation. The book was On the Road, completed -- from start to finish -- in only three weeks. And he used just one long, scrolled piece of paper, improvising endlessly, just like a jazz musician caught up in the excitement of spontaneous creation.

At least, that's how the story goes. Reality was, of course, a little different. Like the highly trained jazz musicians he was emulating, Kerouac actually spent a good deal of time preparing for that creative eruption. But when On the Road came out and his popularity exploded, all the groundwork got lost as people latched onto the myth.

For Morning Edition, Special Correspondent Renée Montagne gets to the bottom of Kerouac's famous novel. As part of Present at the Creation, NPR's ongoing series on the origins of cultural and artistic icons, she digs past the popular story to get into the inspiration, writing process, and public reaction that helped make On the Road a classic.

By the time fame crashed on his doorstep in 1957, Kerouac had already been done with On the Road for several years, but he hadn't found much early success getting someone to publish the book. It could have been that America wasn't ready for his stream-of-consciousness tale of jazz, sex, and fast, aimless driving on an open road. He would soon be a literary star, but on the eve of the book's publication, Kerouac actually had to borrow money for a bus ticket to New York from his girlfriend at the time, Joyce Johnson.

Johnson remembers walking down to the newsstand the morning that The New York Times reviewed On the Road. They opened up the paper to find a rave. Says Johnson, "Jack went to bed obscure and woke up famous."

The Times reviewer, Gilbert Millstein, wrote: "Just as, more than any other novel of the Twenties, The Sun Also Rises came to be regarded as the testament of the 'Lost Generation,' so it seems certain that On the Road will come to be known as that of the 'Beat Generation.'"

Not all the reviews were so positive, but the publicity gave Kerouac an almost instant injection of fame. Johnson recalls mobs around him at parties. "Women wanted him to make love to them and all the men wanted to fight him," she says. "People kept mixing him up with Neal Cassady." Unfortunately, he wasn't as prepared to deal with the onslaught of attention as his friend, on whom he based the magnetic character of Dean Moriarty, might have been.

Carolyn Cassady, the wife of Neal and hostess to Kerouac during the writing of On the Road, remembers her houseguest and friend as a much more sensitive, disciplined writer than most of his readers imagined. She says Kerouac was always on the lookout for material, which he would record in a tiny notebook until he slowed down enough to pull the fragments together.

"When he got somewhere where he could settle down for a few weeks or months he would write like crazy," Cassady remembers. He was "sort of a dynamo, but he'd been collecting the notes and things all the time he was roaming around."

Kerouac didn't like all the attention that was focused on the faster aspects of his life: the speed of his writing, the music he listened to, the overnight success. But the legend surrounding On the Road persisted in part because some of the story was true. Though the book didn't really emerge from his brain fully formed in those frantic three weeks of writing, he did type it up on a single scroll of paper, 120 feet long.

Jim Canary of Indiana University has spent a great deal of time with this document since the owner of the Indianapolis Colts purchased it last year for $2.4 million. "[Kerouac] wanted to be able to just go on uninterruptedly as much as possible," Canary explains. "And that seems to be what he's done. There are basically no paragraph marks to speak of. It just goes and goes and goes."

While the story about the method of its creation has fascinated readers, On the Road continues to affect audiences because of what Kerouac put into the novel. "Whatever you feel, that's the way jazz musicians do it," says Kerouac scholar Douglas Brinkley. However, he continues, "What Jack Kerouac also knew was that... people like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie were skilled, crafted musicians. This didn't just come out of a whim."

Kerouac, who died in 1969 at the age of 47, may have eventually been done in by his own creation. He turned to alcohol, in part to deal with the stresses of fame, and never recovered. Part of that fame was predicated on the notion that he was solely an antiestablishment writer, says Brinkley, who thinks this idea does a disservice to Kerouac's message.

"If you read On the Road, it's a valentine to the United States," he says. "All this is pure poetry for almost a boy's love for his country that's just gushing in its adjectives and descriptions. You know, Kerouac used to say, 'Anybody can make Paris holy, but I can make Topeka holy.'"

In Depth

Search for more NPR reports on Jack Kerouac.

Search for more NPR reports on Jack Kerouac.

Other Resources

• Visit the Literary Kicks site for articles on Kerouac and the Beat Generation.

• Read Gilbert Millstein's New York Times review of On the Road as well as other Kerouac reviews and articles in the newspaper.

• Read an interview with Carolyn Cassady, Neal Cassady's widow, in which she discusses On the Road.

• Read Kerouac's writing technique outline and his "Essentials of Spontaneous Prose."

• Listen to more Kerouac in his own voice at the Kerouac Speaks site.

• Take Denver's Beat Poetry Driving Tour.

• Visit the Beat Page to read about Beat writers and see excerpts of their works.

• Review a variety of On the Road book covers from the United States and abroad.

• The American Museum of Beat Art offers a look at Beat Generation writers, poets and artists.

• Explore links to more Web sites about Kerouac and others in the Beat Generation.

At least, that's how the story goes. Reality was, of course, a little different. Like the highly trained jazz musicians he was emulating, Kerouac actually spent a good deal of time preparing for that creative eruption. But when On the Road came out and his popularity exploded, all the groundwork got lost as people latched onto the myth.

For Morning Edition, Special Correspondent Renée Montagne gets to the bottom of Kerouac's famous novel. As part of Present at the Creation, NPR's ongoing series on the origins of cultural and artistic icons, she digs past the popular story to get into the inspiration, writing process, and public reaction that helped make On the Road a classic.

By the time fame crashed on his doorstep in 1957, Kerouac had already been done with On the Road for several years, but he hadn't found much early success getting someone to publish the book. It could have been that America wasn't ready for his stream-of-consciousness tale of jazz, sex, and fast, aimless driving on an open road. He would soon be a literary star, but on the eve of the book's publication, Kerouac actually had to borrow money for a bus ticket to New York from his girlfriend at the time, Joyce Johnson.

Johnson remembers walking down to the newsstand the morning that The New York Times reviewed On the Road. They opened up the paper to find a rave. Says Johnson, "Jack went to bed obscure and woke up famous."

The Times reviewer, Gilbert Millstein, wrote: "Just as, more than any other novel of the Twenties, The Sun Also Rises came to be regarded as the testament of the 'Lost Generation,' so it seems certain that On the Road will come to be known as that of the 'Beat Generation.'"

Not all the reviews were so positive, but the publicity gave Kerouac an almost instant injection of fame. Johnson recalls mobs around him at parties. "Women wanted him to make love to them and all the men wanted to fight him," she says. "People kept mixing him up with Neal Cassady." Unfortunately, he wasn't as prepared to deal with the onslaught of attention as his friend, on whom he based the magnetic character of Dean Moriarty, might have been.

Carolyn Cassady, the wife of Neal and hostess to Kerouac during the writing of On the Road, remembers her houseguest and friend as a much more sensitive, disciplined writer than most of his readers imagined. She says Kerouac was always on the lookout for material, which he would record in a tiny notebook until he slowed down enough to pull the fragments together.

"When he got somewhere where he could settle down for a few weeks or months he would write like crazy," Cassady remembers. He was "sort of a dynamo, but he'd been collecting the notes and things all the time he was roaming around."

Kerouac didn't like all the attention that was focused on the faster aspects of his life: the speed of his writing, the music he listened to, the overnight success. But the legend surrounding On the Road persisted in part because some of the story was true. Though the book didn't really emerge from his brain fully formed in those frantic three weeks of writing, he did type it up on a single scroll of paper, 120 feet long.

Jim Canary of Indiana University has spent a great deal of time with this document since the owner of the Indianapolis Colts purchased it last year for $2.4 million. "[Kerouac] wanted to be able to just go on uninterruptedly as much as possible," Canary explains. "And that seems to be what he's done. There are basically no paragraph marks to speak of. It just goes and goes and goes."

While the story about the method of its creation has fascinated readers, On the Road continues to affect audiences because of what Kerouac put into the novel. "Whatever you feel, that's the way jazz musicians do it," says Kerouac scholar Douglas Brinkley. However, he continues, "What Jack Kerouac also knew was that... people like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie were skilled, crafted musicians. This didn't just come out of a whim."

Kerouac, who died in 1969 at the age of 47, may have eventually been done in by his own creation. He turned to alcohol, in part to deal with the stresses of fame, and never recovered. Part of that fame was predicated on the notion that he was solely an antiestablishment writer, says Brinkley, who thinks this idea does a disservice to Kerouac's message.

"If you read On the Road, it's a valentine to the United States," he says. "All this is pure poetry for almost a boy's love for his country that's just gushing in its adjectives and descriptions. You know, Kerouac used to say, 'Anybody can make Paris holy, but I can make Topeka holy.'"

In Depth

Search for more NPR reports on Jack Kerouac.

Search for more NPR reports on Jack Kerouac.

Other Resources

• Visit the Literary Kicks site for articles on Kerouac and the Beat Generation.

• Read Gilbert Millstein's New York Times review of On the Road as well as other Kerouac reviews and articles in the newspaper.

• Read an interview with Carolyn Cassady, Neal Cassady's widow, in which she discusses On the Road.

• Read Kerouac's writing technique outline and his "Essentials of Spontaneous Prose."

• Listen to more Kerouac in his own voice at the Kerouac Speaks site.

• Take Denver's Beat Poetry Driving Tour.

• Visit the Beat Page to read about Beat writers and see excerpts of their works.

• Review a variety of On the Road book covers from the United States and abroad.

• The American Museum of Beat Art offers a look at Beat Generation writers, poets and artists.

• Explore links to more Web sites about Kerouac and others in the Beat Generation.

Jack Kerouac Listening to Himself on the Radio, New York City, 1959

Photo: © John Cohen from There is No Eye: John Cohen Photographs, published by powerHouse Books, 2001. Courtesy of Deborah Bell, New York

View enlargement.

Jack Kerouac reads from On the Road on The Steve Allen Plymouth Show in 1959.

Photo: Kerouac, a Film by John Antonelli © 1995 John Antonelli and Mystic Fire Video

Watch a video clip.

Kerouac typed the manuscript for On The Road on a continuous roll of paper. Twelve-foot- long sheets of tracing paper were taped together to make one continuous roll. The scroll is about 120 feet long.

Photo: Chip Grabow, NPR News

See a closer view.

Neal Cassady, left, and Jack Kerouac on the cover of a recent edition of On the Road.

Cover used by permission of Viking Penguin, a division of Penguin Putnam Inc.; Cover photo: Carolyn Cassady

Read excerpts.

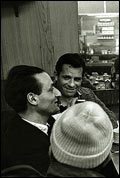

(Clockwise) Poet Gregory Corso (back of head to camera), artist Larry Rivers and Jack Kerouac in New York City, 1959.

Photo: © John Cohen from There is No Eye: John Cohen Photographs, published by powerHouse Books, 2001. Courtesy of Deborah Bell, New York

View enlargement.